|

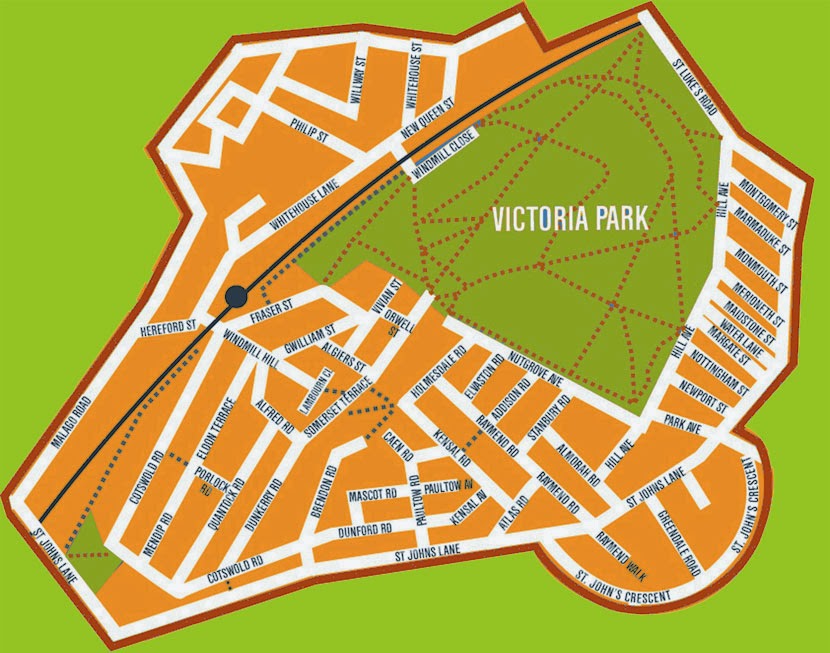

| Eric Ravilious, Alphabet design, c1937 |

Some initial thoughts come to mind. Perhaps we citizens of the Facebook Age yearn for a simpler past, and find in those railway compartments and cottage rooms a suitably nostalgic escape. Perhaps - as some people believe, though I'm not one of them - Ravilious epitomises the Englishness some are so fearful of losing. More interestingly, I wonder whether there's a generational thing going on, with the 1930s now possessing some of the allure of the Edwardian or Victorian periods. But that doesn't explain why people love Ravilious and not one or other of his more famous or successful peers.

Indeed, there's no end of nostalgic English art we could all swoon over, but only one Eric Ravilious - it's something about those watercolours and designs in particular that appeals to the 21st century eye. Perhaps the real question we should be asking is why it has taken so long for the art-loving public to discover them. Was there simply a natural hiatus after the artist's premature death in 1942? Or a reaction against the 'Romantic Moderns' of the 1930s?

It's intriguing to note that Ravilious and Bawden began their careers just as several forgotten artists of the previous century were remembered. It was in the aftermath of the Great War that John Sell Cotman, Francis Towne and Samuel Palmer were taken up by a new generation, having been ignored for years. In the 1920s, as now, anxiety about the present fuelled interest in the past - in stone circles and earthworks, the buried treasure of Egypt and Sutton Hoo.

But if this helps us understand Ravilious's choice of medium and subject matter, it still doesn't bring us much closer to answering our question. Designs like the Alphabet (above) were popular enough when they first appeared, but today they have cult status. People take pilgrimages to the sites of Ravilious paintings, whether Cuckmere Haven or Great Bardfield. I meet a lot of fans when I give lectures and sign books, and they tend to be thoughtful, enthusiastic and curious to find out more. Art critics have often described the artist's work as emotionally cool or distant, but both paintings and designs seem to evoke powerful feelings in all kinds of people.

So we can think about changes in fashion, historical cycles, cultural anxieties and so on, but in the end - as with any artist - we come back to the work. There's something about those tiny engraved vignettes, those lighthouses and silent hills - something that pulls us in? But what?

Now there's a question...

I'll be doing my best to address it next Tuesday at St Brides in Fleet Street, and there will be an opportunity afterwards to have your say. Hope to see you there!